Janitorial services represent one of the great paradoxes of modern life: the work is essential, yet the workers remain largely invisible. Every morning, office workers arrive to find their desks cleared, bins emptied, and floors gleaming. Shoppers browse stores with spotless aisles and pristine toilets. Students enter classrooms where yesterday’s chaos has been restored to order. Yet few pause to consider the people who made this possible, often working through the night whilst the rest of us slept. This invisibility is not accidental. It is woven into how we organise work, value labour, and structure our built environment.

The Architecture of Overlooked Labour

Walk into any modern office building at half past seven in the evening. The daytime workers have departed, leaving behind the detritus of their productivity: coffee cups on desks, papers scattered across conference tables, rubbish overflowing from bins. Within hours, a transformation will occur. By morning, every surface will be clean, every bin emptied, every trace of the previous day erased. This nightly resurrection happens because of janitors who move through spaces designed to make them inconspicuous.

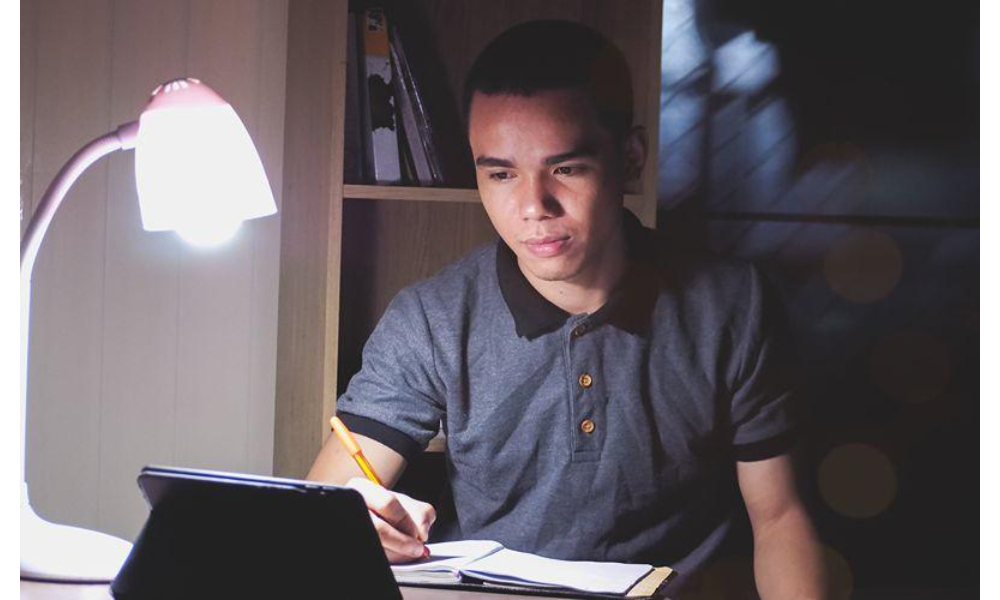

The scheduling itself ensures separation. Janitorial service teams typically work early mornings or late evenings, outside regular business hours. This arrangement suits building managers who prefer cleaning to happen when it will not disrupt other activities. But it also means janitors rarely interact with the people whose spaces they maintain. They become ghosts in the machine, necessary but unseen.

What the Work Actually Involves

Professional janitorial work is far more complex than most people imagine. It is not simply a matter of pushing a mop or emptying bins. The scope encompasses:

• Surface care expertise

Understanding which cleaning agents work on which materials without causing damage or leaving residue

• Health and safety protocols

Following proper procedures for handling biological hazards, chemical storage, and waste disposal

• Equipment operation

Managing industrial cleaning machines, from floor buffers to carpet extractors to high-reach window cleaning tools

• Time management

Completing extensive task lists within fixed windows, often with insufficient staffing

• Problem-solving

Addressing unexpected situations, from plumbing emergencies to spills requiring immediate attention

• Customer service

Responding to requests and complaints whilst maintaining professional demeanour despite often being treated as beneath notice

The Singapore Context

Singapore’s janitorial services sector reveals both progress and persistent challenges. The nation has made notable efforts to professionalise the industry through initiatives like the Progressive Wage Model, which establishes minimum wages that increase with training and experience. The Environmental Services Industry Transformation Map aims to improve working conditions and career prospects.

Yet significant issues remain. As one veteran cleaner in Singapore observed, “People look through you. You clean the table they are sitting at, and they do not move their laptops or say thank you. You are furniture to them.” This experience of social invisibility affects workers’ dignity as profoundly as wages affect their material security.

The sector also grapples with an ageing workforce. Many janitors in Singapore are older workers who entered the profession after other career options closed. The physical demands of the work, from prolonged standing to repetitive motions to exposure to cleaning chemicals, take a cumulative toll that accelerates with age.

The Economics of Essential Work

Janitorial services exist in a brutal economic squeeze. Clients want the lowest possible cost. Contractors compete by cutting wages and benefits. Workers bear the consequences. The result is an industry where people performing essential labour often struggle to meet basic needs.

Consider the mathematics: a cleaner might be responsible for 10,000 square metres of space to be cleaned within a four-hour shift. That works out to roughly 42 square metres every minute, with no allowance for breaks, equipment issues, or unexpected messes. The pressure is relentless. Miss a spot, and there is a complaint. Take too long, and management questions your efficiency. The work demands both speed and thoroughness, though these qualities often conflict.

Outsourcing intensifies these pressures. When organisations contract janitorial work to external firms rather than employing cleaners directly, it creates distance and dilutes responsibility. The cleaners are not “our employees”; they work for the contractor. This separation makes it easier to ignore poor conditions or resist improvements that might increase costs.

Dignity and Recognition

Yet there is nothing inherently undignified about cleaning. The work itself, maintaining spaces where others can live and work comfortably, serves a vital social function. What strips dignity is not the nature of the labour but how it is valued and how workers are treated.

Some organisations are beginning to recognise this. Initiatives that introduce cleaners by name, include them in workplace communications, and acknowledge their contributions help restore visibility and respect. Training programmes that offer genuine skill development and career progression provide pathways beyond entry-level positions. Fair wages and benefits signal that the work matters.

The Path to Change

Improving conditions in janitorial work requires structural changes. Living wages must become standard, not exceptional. Direct employment should replace precarious contracting arrangements. Training and advancement opportunities need expansion. Perhaps most fundamentally, the social attitudes that render cleaners invisible must be challenged.

This is not charity; it is justice. The people who maintain our offices, schools, hospitals, and public spaces deserve recognition for their contribution and compensation that reflects the work’s value. Every time we enter a clean building, we are benefiting from someone else’s labour. Acknowledging that fact, treating those workers with respect, and ensuring they can live with dignity is not too much to ask. The quality of our society is measured not by how we treat those at the top but by how we treat those whose work makes everyone else’s possible. The commitment to excellent janitorial services must include a commitment to the people who provide them.

Comments